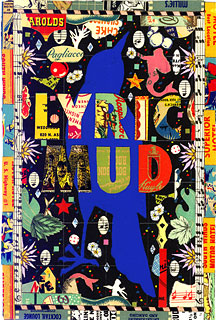

This article is about ETA blogger David Cutler and his new book, The Savvy Musician. It was written by Andrew Druckenbrod and ran in in Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on Sunday August 9th, 2009. The picture was illustrated by Stacy Innerst/Post-Gazette. I highly recommend David’s book if you want to learn how to become a “savvy musician!”

Overpopulation, poverty and stagnation: The way the classical music industry is described these days you’d think it’s a Third World country. The recession has made an already tough existence even tougher for music students and those already looking for jobs.

Overpopulation, poverty and stagnation: The way the classical music industry is described these days you’d think it’s a Third World country. The recession has made an already tough existence even tougher for music students and those already looking for jobs.

“It is an extraordinarily difficult time to compete for traditional full-time jobs, like those in academia and in orchestras,” says David Cutler, a music professor at Duquesne University. “The market is over-saturated with talent, people are keeping their jobs for longer and orchestras are cutting back, not adding.”

But have things really gotten so bad that a student should follow that classic parental advice and go to medical or law school instead?

Not according to a new movement called music entrepreneurship that is gaining ground at schools around the country. Cutler is among several professors at the forefront of this change in attitude; his book, “The Savvy Musician” (Helius Press, $19.99, due out in November) is a guide to navigating these uncertain waters, targeted to those facing the “real world.”

More information about “The Savvy Musician”

• Advance copies of “The Savvy Musician,” to be released widely in November, can be purchased at http://www.savvymusician.com.

• Have you ventured off the beaten path for your musical career? If so, we would like to hear about it. Go to ClassicalMusings to share your story.

Among the topics, the book discusses details of marketing, recording and grant writing, but it spends most of its time articulating bigger concepts of the “entrepreneurial mind-set.”

For years, conventional wisdom has been that leadership in the classical music industry should work to increase demand so that more young musicians can get jobs. Better funding, it is said, should be found to expand orchestras and develop audiences, and music should be cultivated at all levels. But for advocates of entrepreneurship such as Cutler, it is the musician who must adapt to the shrinking and changing marketplace.

“The days of being just a classical violinist or jazz saxophonist are over,” says Cutler. “The musician of the future considers the whole package. You should be a great player, but that is not the goal, but the minimum.”

Many feel that music education in America — slow to change in the past half century — has failed students in this regard. “We have created more extremely talented musicians than ever before,” says Cutler. “But in curriculum, we have completely ignored many other essential issues such as how to make a living or how to make an difference in society.”

Cutler and others see the new environment brimming with possibilities, even as it has shut down or backlogged traditional routes. “It is hard, but there are opportunities that weren’t there before,” he says. “If [your quartet] tries to get a gig at Carnegie Hall, you might be up against 300 quartets, but if you go to a smaller community you can make it work.”

One sterling example is the Ying String Quartet, which began its career in the 1990s as the resident quartet of Jesup, Iowa, a farm town of 2,000 people. It performed in homes, schools, churches and banks, with a philosophy that “concert music can also be a meaningful part of everyday life.”

The Ying Quartet’s off-the-beaten path garnered national interest and forged its musicality as a group so that today the quartet is considered one of the top in the world, playing more typical venues such as Carnegie Hall.

Another alternative route was taken by a group of Chicago musicians who created a split business model. They formed two companies, a nonprofit called Fifth House Ensemble that gives concerts and education and a for-profit called Amarante Ensembles that plays parties and gatherings. Having both puts the musicians on more even financial footing and spreads out risk.

Other examples of innovative thinking abound, from the genre-bending and branding-savvy Kronos Quartet to John Cimino, a baritone who uses music-making as a metaphor for creativity and leadership in presentations to Fortune 500 corporations.

So, the problem isn’t that there is a glut of musicians, Cutler and others argue, but that there are too many seeking traditional jobs without really considering the alternatives. Colleges and conservatories traditionally have not equipped students with the right tools to prosper in a shrinking marketplace.

Gary Beckman, founder of the Arts Entrepreneurship Educator’s Network, realized this deficiency firsthand long before the economy laid it bare for all to see.

“I went through undergrad and grad school, and I saw many musicians who were more than capable, but because they didn’t get training and information about economic reality they didn’t go on to play,” he says. “So many are lost each year.”

Beckman, Cutler and others at schools, such as the University of South Carolina, the Eastman School of Music and the University of Colorado, are on the cutting edge of entrepreneurship programs and courses emerging to train students to forge their own paths.

“We need students that have a broad view about their careers,” says Beckman, who is a visiting professor in South Carolina’s Institute for Leadership and Engagement in Music. He estimates that as many as 100 colleges offer at least one course in arts entrepreneurship. “In the context of 6,000 universities with arts departments, that it isn’t taking [academia] by storm, but steps are being made and the seeds are starting to germinate.”

“Entrepreneurship is gaining traction because it offers something significant to every student considering a career,” says Jeffrey Nytch, director of the University of Colorado’s Entrepreneurship Center for Music. It’s not just about sending musicians to the campus career center, he says, but totally rethinking their career.

“Deans and provosts are behind it,” says Beckman. “Everyone realizes there is a problem, but it is a very delicate negotiation between faculty, accreditation, community, students, funders, administration. About half a dozen colleges add a course every year, and I think there will be a explosion in the next three to five years.”

Duquesne University’s Mary Pappert School of Music will offer its first classes on entrepreneurship and leadership this fall, coordinated by Cutler, who joined the faculty in 2001. Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh do not offer entrepreneurship courses, but both bring in speakers on the subject and address the business of music on a one-on-one manner. “Many people have great ideas, but if you have the skills to make them a reality, then it is a success,” says Noel Zahler, head of CMU’s School of Music.

“We have an ethical responsibility to address these issues,” says Cutler, who also will re-configure Duquesne’s contemporary ensemble to be student-driven to “function like a chamber ensemble would in the real world.”

“This is about empowering students,” says Beck. He thinks Cutler’s book brings that same confidence to those in schools or already struggling to make a living as musicians. “What David has done has helped to outline how broad an education one needs to have a career in music.”

Join and Cast Ventures: Two Art (Intermedia) students, Jennifer C. and Catherine A., are producing a field guide to the downtown Phoenix arts scene that is itself a work of art.

Join and Cast Ventures: Two Art (Intermedia) students, Jennifer C. and Catherine A., are producing a field guide to the downtown Phoenix arts scene that is itself a work of art. Radio Healer: Led by Arts, Media Engineering (AME) graduate student Christopher M., Radio Healer presents mediated performances that foster intercultural dialogue in Native communities.

Radio Healer: Led by Arts, Media Engineering (AME) graduate student Christopher M., Radio Healer presents mediated performances that foster intercultural dialogue in Native communities. Dance and Health Together Awards: Led by undergraduate Dance major Mary P., the DaHT Awards is a combination of dance recognition award and fundraising enterprise benefiting the Susan G. Komen Foundation.

Dance and Health Together Awards: Led by undergraduate Dance major Mary P., the DaHT Awards is a combination of dance recognition award and fundraising enterprise benefiting the Susan G. Komen Foundation. Co-op Film Productions – Film and Media Production/Marketing student Chelsea R. and her team are creating a support infrastructure for student collaboration across arts and design disciplines.

Co-op Film Productions – Film and Media Production/Marketing student Chelsea R. and her team are creating a support infrastructure for student collaboration across arts and design disciplines. Different from What? Film Festival – AME graduate student Lisa T. in collaboration with Education student Federico W. is producing a film festival focused on films by, for, and about adults with disabilities.

Different from What? Film Festival – AME graduate student Lisa T. in collaboration with Education student Federico W. is producing a film festival focused on films by, for, and about adults with disabilities. Scratch Theory – Filmmaking Practices major Chris G. and his collaborators are developing a software/hardware interface that will first notate and then play back via synthesizer DJ scratching.

Scratch Theory – Filmmaking Practices major Chris G. and his collaborators are developing a software/hardware interface that will first notate and then play back via synthesizer DJ scratching.

By our very nature, entrepreneurial artists always have too much to do, with an eruption of great ideas and initiatives in the pipeline. Finding time to address everything can be tough. As a result, many artists make little forward progress on important life goals year after year, despite the reality that they’re constantly frantic with work. If this scenario sounds familiar, here are some tips that can help:

By our very nature, entrepreneurial artists always have too much to do, with an eruption of great ideas and initiatives in the pipeline. Finding time to address everything can be tough. As a result, many artists make little forward progress on important life goals year after year, despite the reality that they’re constantly frantic with work. If this scenario sounds familiar, here are some tips that can help: